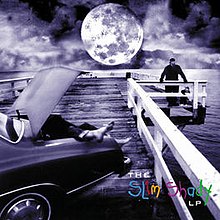

The Slim Shady LP

| The Slim Shady LP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | February 23, 1999 | |||

| Recorded | 1997–1998[1] | |||

| Studio | Studio 8 (Ferndale, Michigan) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 59:39 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer |

| |||

| Eminem chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Slim Shady LP | ||||

| ||||

The Slim Shady LP is the second studio album by American rapper Eminem. It was released through Aftermath Entertainment, WEB Entertainment, and Interscope Records on February 23, 1999.[2] Recorded in Ferndale, Michigan following Eminem's recruitment by Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine, the album features production from Eminem himself, alongside Dr. Dre and the Bass Brothers. Featuring West Coast hip hop, G-funk, and horrorcore musical styles, the majority of The Slim Shady LP's lyrical content was written from the perspective of Eminem's alter ego, named Slim Shady. The alter ego was introduced on his 1997 extended play Slim Shady EP, and concluded on his 2024 studio album The Death of Slim Shady (Coup de Grâce). The album contains cartoonish depictions of violence and heavy use of profanity, which Eminem described as horror film-esque, in that it is solely for entertainment value. Although many of the lyrics on the album are considered to be satirical, Eminem also discusses his frustrations of living in poverty.

The Slim Shady LP debuted at number two on the US Billboard 200, just below TLC's FanMail, and number one on the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart. It was a critical and commercial success, with critics praising Eminem for his unique lyrical style, dark humor lyrics, and unusual personality.[3] "My Name Is" was the album's first single, and became Eminem's first entry on the US Billboard Hot 100. The Slim Shady LP won Best Rap Album at the 2000 Grammy Awards, while "My Name Is" won Best Rap Solo Performance. In 2000, The Slim Shady LP was certified quadruple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). It is often mentioned in lists of the greatest albums of all time. While The Slim Shady LP's success turned Eminem from an underground rapper into a high-profile celebrity, he became a highly controversial figure due to his lyrical content, which some perceived to be misogynistic and a negative influence on American youth.

Background

[edit]Eminem, whose real name is Marshall Bruce Mathers III, began rapping at the age of 14. In 1996, Eminem released his debut studio album, Infinite, in which was recorded at the Bassmint, a recording studio being owned by the Bass Brothers, was released under their independent record label, Web Entertainment.[4] Infinite was a commercial failure and was largely ignored by Detroit radio stations. This experience greatly influenced his lyrical style: "After that record, every rhyme I wrote got angrier and angrier. A lot of it was because of the feedback I got. Motherfuckers was like, 'You're a white boy, what the fuck are you rapping for? Why don't you go into rock & roll?' All that type of shit started pissing me off."[5] After the release of Infinite, Eminem's personal struggles and abuse of methadone and alcohol culminated in a suicide attempt.[6]

The failure of Infinite inspired Eminem to create the alter ego Slim Shady: "Boom, the name hit me, and right away I thought of all these words to rhyme with it."[5] Slim Shady served as Eminem's vent for his frustration and rage to the world. In the spring of 1997, he recorded the eight-song extended play Slim Shady EP. During this time, Eminem and his girlfriend Kim Scott lived in a high-crime neighborhood with their newborn daughter Hailie, where their house was burglarized numerous times.[5] After being evicted from his home, Eminem traveled to Los Angeles to participate in the Rap Olympics, an annual nationwide rap battle competition. He placed second, and the staff at Interscope Records who attended the Rap Olympics sent a copy of the Slim Shady EP to company CEO Jimmy Iovine.[5] Iovine played the tape for hip hop producer Dr. Dre, founder of Aftermath Entertainment. Dr. Dre recalled, "In my entire career in the music industry, I have never found anything from a demo tape or a CD. When Jimmy played this, I said, 'Find him. Now.'"[5] Some urged Dr. Dre not to take a chance on Eminem because he was white. Dr. Dre responded, "I don't give a fuck if you're purple. If you can kick it, I'm working with you."[7]

Recording

[edit]

The Slim Shady LP was recorded at Studio 8 at 430 8 Mile Road in Ferndale, Michigan.[8] Eminem, who had idolized Dr. Dre since listening to his group N.W.A as a teenager, was nervous to work with him on the album: "I didn't want to be starstruck or kiss his ass too much ... I'm just a little white boy from Detroit. I had never seen stars, let alone Dr. Dre."[9] However, Eminem became more comfortable working with Dr. Dre after a series of highly productive recording sessions. The recording process generally began with Dr. Dre creating a beat and Eminem using the tracks as a template for his freestyle raps; "Every beat he would make, I had a rhyme for", Eminem recalled.[10] He later said: "Every time I sat down with a pen, everything was just like: fuck you, fuck this, fuck them, fuck that, fuck the world, fuck what everybody thinks. Fuck them." On the first day of recording, Eminem and Dr. Dre finished "My Name Is" in an hour.[5] Three other songs, including "Role Model", were also recorded that day.[9]

"'97 Bonnie & Clyde", which was formerly featured on the Slim Shady EP as "Just the Two of Us", was re-recorded for The Slim Shady LP to feature his daughter Hailie's vocals. Because the song focuses on disposing of his girlfriend's corpse, Eminem was not comfortable with explaining the situation to Kim, and instead told her that he would be taking Hailie to Chuck E. Cheese's.[5] He explained, "When she found out I used our daughter to write a song about killing her, she fucking blew. We had just got back together for a couple of weeks. Then I played her the song and she bugged the fuck out." Eminem also said, "When she (Hailie) gets old enough, I'm going to explain it to her. I'll let her know that Mommy and Daddy weren't getting along at the time. None of it was to be taken too literally, although at the time I wanted to fucking do it."[5] Eminem asked Marilyn Manson to guest appear on the song, but the singer declined because he felt that the song was "too misogynistic".[11] The song "Guilty Conscience" contains a humorous reference to an occasion in which Dr. Dre assaulted Dee Barnes. Having only known Dr. Dre for a few days, Eminem was anxious about how he would react to such a line, and to his relief, Dr. Dre "fell out of his chair laughing" upon hearing the lyric.[12]

"Ken Kaniff", a skit involving a prank call to Eminem, featured fellow Detroit rapper Aristotle. After a falling out between the two in the wake of Eminem's breakthrough success, Eminem instead played Ken Kaniff on skits on future albums. Ken Kaniff would end up appearing in more Eminem albums over the course of his career and was last heard in The Death of Slim Shady (Coup de Grâce).[13] Another skit, "Bitch", is an answering machine message in which Zoe Winkler, daughter of actor Henry Winkler, tells a friend that she was disgusted by Eminem's music. He met and had dinner with her in order to get permission to use the recording on the album.[14] During the mixing process of The Slim Shady LP, at the same time, Kid Rock was recording his fourth studio album, Devil Without a Cause; being friends with Kid Rock, Eminem asked Kid Rock to record scratching for Eminem's song "Just Don't Give A Fuck", which appears on both Slim Shady EP & The Slim Shady LP; in return, Eminem delivered a guest rap verse on Kid Rock's song "Fuck Off" for Devil Without a Cause.[15]

Production

[edit]The album's production was handled primarily by Dr. Dre, the Bass Brothers, and Eminem.[18][19] The beats have been compared to West Coast hip hop and G-funk musical styles.[20] Kyle Anderson of MTV wrote that "The beats are full of bass-heavy hallucinations and create huge, scary sandboxes that allow Em to play."[18] According to the staff at IGN, "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" is backed by the "lulling serenity of a super silky groove".[16] "Cum on Everybody"; which features guest vocals from American singer Dina Rae[21] contains an upbeat dance rhythm, while "My Name Is", which is built around a sample from British musician Labi Siffre's "I Got The...", features a prominent bassline and psychedelic-style keyboards.[18][16][17] "I'm Shady" was originally written over a Sade track, but after hearing a sample of Curtis Mayfield's "Pusherman" in Ice-T's song "I'm Your Pusher", Eminem decided it would be more fitting to use "Pusherman".[22]

Eminem's vocal inflection on the album has been described as a "nasal whine"; Jon Pareles of The New York Times likened his "calmly sarcastic delivery" to "the early Beastie Boys turned cynical".[23] Writing for the Chicago Tribune, columnist Greg Kot compared the rapper's vocals to "Pee-wee Herman with a nasal Midwestern accent".[24] A skit entitled "Lounge" appears before "My Fault" featuring Eminem and the Bass Brothers imitating rat pack crooners. Jeff Bass came up with the line "I never meant to give you mushrooms" for the skit, which in turn inspired Eminem to write "My Fault".[25]

Lyrical themes

[edit]Many of the songs from The Slim Shady LP are written from the perspective of Eminem's alter ego, Slim Shady, and contain cartoonish depictions of violence, which he refers to as "made-up tales of trailer-park stuff".[27] The rapper explained that this subject matter is intended for entertainment value, likening his music to the horror film genre: "Why can't people see that records can be like movies? The only difference between some of my raps and movies is that they aren't on a screen."[28] Some of the lyrics have also been considered to be misogynistic by critics and commentators.[29] Eminem acknowledged the accusations, and clarified, "I have a fairly salty relationship with women ... But most of the time, when I'm saying shit about women, when I'm saying 'bitches' and 'hoes', it's so ridiculous that I'm taking the stereotypical rapper to the extreme. I don't hate women in general. They just make me mad sometimes.'"[29] Despite the album's explicit nature, Eminem refused to say the word "nigga" on the album, noting, "It's not in my vocabulary."[29] The Slim Shady LP begins with a "Public Service Announcement" introduction performed by producer Jeff Bass of the Bass Brothers, and serves as a sarcastic disclaimer discussing the album's explicit lyrical content.[30] Later in the album, a skit entitled "Paul" features a phone call from Paul Rosenberg to Eminem telling him to "tone down" his lyrics.[31]

"Guilty Conscience" is a concept song featuring Dr. Dre. The song focuses on a series of characters who are faced with various situations, while Dr. Dre and Eminem serve as the "angel" and "devil" sides of the characters' conscience, respectively.[18] The song draws inspiration from a scene in the 1978 comedy film National Lampoon's Animal House, in which a man takes advice from an angel and devil on his shoulder while considering raping an unconscious girl at a party.[28] In the film, he ends up deciding not to go through with the rape, but in "Guilty Conscience", the outcome is unclear.[28] On "My Fault", Eminem tells the story of a girl who overdoses on psychedelic mushrooms at a rave.[32] "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" features Eminem convincing his infant daughter to assist him in disposing of his wife's corpse. It is an epilogue to the song "Kim", although "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" was released first. Eminem wrote the song at a time in which he felt that Kim was stopping him from seeing his daughter.[28] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of Allmusic explained that "There have been more violent songs in rap, but few more disturbing, and it's not because of what it describes, it's how he describes it -- how the perfectly modulated phrasing enhances the horror and black humor of his words."[19] On the song "Brain Damage", Eminem discusses his childhood experiences with bullies at school, particularly recalling a traumatic incident where he sustained a serious concussion after he was severely beaten by a bully.[33]

Although many of the lyrics on the album are intended to be humorous, several songs depict Eminem's frustrations with living in poverty. When discussing The Slim Shady LP, Anthony Bozza of Rolling Stone described Eminem as "probably the only MC in 1999 who boasts low self-esteem. His rhymes are jaw-droppingly perverse, bespeaking a minimum-wage life devoid of hope, flushed with rage and weaned on sci-fi and slasher flicks."[5] Eminem was inspired to write "Rock Bottom" after being fired from his cooking job at a restaurant days before his daughter's birthday.[5] The song bemoans human dependency on money, discussing its ability to brainwash an individual.[26] He illustrates his struggles to provide for his daughter, describing himself as "discouraged, hungry, and malnourished."[26] "If I Had" follows a similar theme, as he describes living on minimum wage and remarks that he is "tired of jobs starting off at $5.50 an hour".[34] In the song, he expresses his irritation with fitting the "white trash" stereotype.[35]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Sun-Times | |

| Christgau's Consumer Guide | A−[37] |

| Entertainment Weekly | C+[38] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| Melody Maker | |

| NME | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | 8/10[43] |

The album was met with critical acclaim. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic gave the album five stars out of five, praising the rapper's "expansive vocabulary and vivid imagination", adding that "Years later, as the shock has faded, it's those lyrical skills and the subtle mastery of the music that still resonate, and they're what make The Slim Shady LP one of the great debuts in both hip-hop and modern pop music."[19] David Browne of Entertainment Weekly described the album's "unapologetic outrageousness" as a reaction to the "soul positivity" of conscious hip hop, noting that "The Slim Shady LP marks the return of irreverent, wiseass attitude to the genre, heard throughout the album in its nonstop barrage of crudely funny rhymes ... Even pop fans deadened to graphic lyrics are likely to flinch."[38] Soren Baker of the Los Angeles Times gave the album three and a half stars out of four and stated that "He isn't afraid to say anything; his lyrics are so clever that he makes murder sound as if it's a funny act he may indulge in simply to pass the time" but lamented the "sometimes flat production that takes away from the power of Eminem's verbal mayhem."[39]

Many reviewers commented on the album's lyrical content. Gilbert Rodman of Popular Communications states, "Eminem's music contains more than its fair share of misogynistic and homophobic lyrics, but simply to reduce it to these (as many critics do) doesn't help to explain Eminem. It merely invokes a platitude or a sound bite to explain him away."[44] Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone enjoyed the record's comedic nature, writing "Simply put: Eminem will crack you up", but also felt that the misogynistic lyrics grow tiresome, noting that "the wife-killing jokes of '97 Bonnie and Clyde' aren't any funnier than Garth Brooks', and 'My Fault' belongs on some sorry-ass Bloodhound Gang record."[20] Nathan Rabin of The A.V. Club felt that although the album is "sophomoric and uninspired" at times, Eminem's "surreal, ultraviolent, trailer-trash/post-gangsta-rap extremism is at least a breath of fresh air in a rap world that's despairingly low on new ideas."[45] Mike Rubin of Spin noted that "his scenarios are so far-fetched the songs almost never sound as ugly as they actually are."[43] Chris Dafoe of The Globe and Mail opined that "Abused by fellow students and teachers, cheated on by his girlfriend, despised by society, Shady goes over the top now and then - or rather way over the top - but Dre's lean production, full of strange voice and comic interjections, hold things together."[46] Reviewing for The Village Voice in 1999, Robert Christgau called the record a "platinum-bound cause celebre" and, despite succumbing to "dull sensationalism" toward the end, Eminem shows "more comic genius than any pop musician since", possibly, Loudon Wainwright III."[47]

Accolades

[edit]At the 42nd Grammy Awards in 2000, the album won Best Rap Album, while "My Name Is" won Best Rap Solo Performance.[48] Rolling Stone ranked The Slim Shady LP number 275 on its list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time and 33 on its list of the "100 Best Albums of the '90s".[49][50] In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked The Slim Shady LP as the 352nd greatest album of all time on their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. NME ranked it number 248 in its list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[51] Blender ranked it number 49 in its list of The 100 Greatest American Albums of All Time.[52] "Ken Kaniff" was listed as number 15 on Complex's "50 Greatest Hip-Hop Skits" list, while the "Public Service Announcement" introduction to the album, along with the "Public Service Announcement 2000" introduction from The Marshall Mathers LP, was listed as number 50 on the list.[30][53] Spin later included it in their list of "The 300 Best Albums of 1985–2014".[54] It also won Outstanding National Album at the 2000 Detroit Music Awards.[55] In 2015, it was ranked at number 76 by About.com in their list of "100 best hip-hop albums of all time".[56] Christgau later named it among his 10 best albums from the 1990s.[57] In 2022, Rolling Stone ranked The Slim Shady LP number 85 in their list of "The 200 Greatest Rap Albums of all time".[58]

Commercial performance

[edit]In the album's first week of release, The Slim Shady LP sold 283,000 copies, debuting at number two on the Billboard 200 chart behind TLC's FanMail.[59] The record remained on the Billboard 200 for 100 weeks.[60] It also reached number one on the R&B/Hip Hop Albums chart, staying on the chart for 92 weeks.[60] On April 5, 1999, The Slim Shady LP was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America for sales of over one million copies.[61] On November 15, 2000, the album was certified quadruple platinum by the RIAA.[61] "My Name Is", the album's lead single, peaked at number 36 on the Billboard Hot 100, remaining on the chart for ten weeks.[62] The single additionally peaked at number 18 on the magazine's R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, 29 on the Pop Songs chart, and 37 on the Alternative Songs chart.[62] "Guilty Conscience" reached number 56 on the Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, while "Just Don't Give a Fuck" peaked at number 62 on the chart.[63][64]

By November 2013, the album sold 5,437,000 copies in the United States.[65] on the weekly Canadian Albums Chart and remained on the chart for twelve weeks.[60] Additionally, the album was certified triple platinum by the Canadian Recording Industry Association for shipments of over 200,000 units.[66] The album was also certified double platinum in the United Kingdom, where it peaked at number ten on the UK Albums chart and remained on the chart for a total of 114 weeks.[67][68] In Australia, the album peaked at number 49 on the ARIA Chart, and was eventually certified platinum in the country.[69][70] The album had also peaked at the number 20 and 23 chart positions in the Netherlands and New Zealand, respectively. It was certified gold in the Netherlands and platinum in New Zealand.[71][72][73]

Aftermath

[edit]

After the success of The Slim Shady LP, Eminem went from an underground rapper into a high-profile celebrity. Interscope Records awarded him with his own record label, Shady Records; the first artist Eminem signed was rapper and his best friend Proof.[74] Eminem, who had previously struggled to provide for his daughter, noted a drastic change in his lifestyle: "This last Christmas, there were so many fucking presents under the tree ... My daughter wasn't born with a silver spoon in her mouth. But she's got one now. I can't stop myself from spoiling her."[74]

"Anybody who believes kids are naive enough to take this record literally is right to fear them, because that's the kind of adult teenagers hate. [This cause célèbre dares] moralizers to go on the attack while explicitly—but not (fuck you, dickwad) unambiguously—declaring itself a satiric, cautionary fiction".

To promote The Slim Shady LP, Eminem embarked on an extensive tour schedule. He joined the Vans Warped Tour as a last-minute replacement for Cypress Hill, a schedule that included 31 North American dates from June 25 to July 31, beginning in San Antonio and ending in Miami.[75] He often played a show in the afternoon on the Warped Tour, and then drove to another location to perform at a hip hop club at night.[74] During a performance in Hartford, Connecticut near the end of the Warped Tour, Eminem slipped on a puddle of liquid and fell ten feet down off the stage, cracking several ribs.[75][76] He recalled that the stress of his newfound fame led him to drink excessively, and reflected, "I knew I had to slow it down. The fall was like a reminder."[76] However, after receiving medical attention, he was well enough to travel to New York the following day for a performance on Total Request Live.[75]

Eminem also became a highly controversial figure due to his lyrical content. He was labeled as "misogynist, a nihilist and an advocate of domestic violence", and in an editorial by Billboard editor in chief Timothy White, the writer accused Eminem of "making money by exploiting the world's misery."[5] During a radio interview in San Francisco, Eminem reportedly angered local DJ Sista Tamu due to a freestyle about "slapping a pregnant bitch" to the extent that on air she broke a copy of The Slim Shady LP.[76] The rapper defended himself by saying, "My album isn't for younger kids to hear. It has an advisory sticker, and you must be eighteen to get it. That doesn't mean younger kids won't get it, but I'm not responsible for every kid out there. I'm not a role model, and I don't claim to be."[5]

Lawsuits

[edit]On September 17, 1999, Eminem's mother, Deborah Nelson, filed a $10 million lawsuit against him for slander based on his claim that she uses drugs in the line "I just found out my mom does more dope than I do" from "My Name Is".[77][78] After a two-year-long trial, she was awarded $25,000, of which she received $1,600 after legal fees.[77] Eminem was not surprised that his mother had filed the lawsuit against him, referring to her as a "lawsuit queen", and alleging that "That's how she makes money. When I was five, she had a job on the cash register at a store that sold chips and soda. Other than that, I don't remember her working a day in her life."[78] She later filed another lawsuit against him for emotional damages suffered during the first trial, which was later dismissed.[77]

In December 2001, DeAngelo Bailey, a janitor living in Roseville, Michigan who was made the subject of the song "Brain Damage" in which he is portrayed as a school bully, filed a $1 million lawsuit against Eminem for slander and invasion of privacy.[33] Bailey's attorney stated "Eminem is a Caucasian male who faced criticism within the music industry that he had not suffered through difficult circumstances growing up and he was therefore a 'pretender' in the industry ... Eminem used Bailey, his African-American childhood schoolmate, as a pawn in his effort to stem the tide of criticism."[33] In 1982, Eminem's mother unsuccessfully sued the Roseville school district for not protecting her son, as she claimed that attacks from bullies caused him headaches, nausea, and antisocial behavior.[33] Additionally, Bailey had previously admitted to bullying Eminem in the April 1999 issue of Rolling Stone Magazine.[5] The lawsuit was dismissed by judge Deborah Servitto in 2003, who wrote her ruling in the form of rap-like rhyme. She ruled that the lyrics—which include the school principal collaborating with Bailey, and Eminem's entire brain falling out of his head—were too exaggerated for a listener to believe that they were recalling an actual event.[79] The verdict was upheld in 2005, and Bailey's lawyer ruled out any further appeals.[79]

In September 2003, 70-year-old widow Harlene Stein filed suit against Eminem and Dr. Dre on the grounds that "Guilty Conscience" contains an unauthorized sample of "Go Home Pigs" composed for the film Getting Straight by her husband, Ronald Stein, who died in 1988.[80] Although the album's liner notes state that the song contains an interpolation of "Go Home Pigs", Stein is not credited as a composer and his wife was not paid royalties for use of the song.[80] The lawsuit requested for 5 percent of the retail list price of 90 percent all of the copies of the record sold in America, and 2.5 percent of the retail price of 90 percent of the copies of the album sold internationally.[80] The suit was dismissed in June 2004 for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.[81]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Marshall "Eminem" Mathers and the Bass Brothers (Mark Bass and Jeff Bass), except where noted

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Public Service Announcement" | 0:33 | ||

| 2. | "My Name Is" |

| Dr. Dre | 4:28 |

| 3. | "Guilty Conscience" (featuring Dr. Dre) |

|

| 3:19 |

| 4. | "Brain Damage" |

| 3:46 | |

| 5. | "Paul (skit)" | 0:15 | ||

| 6. | "If I Had" | 4:05 | ||

| 7. | "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" | 5:16 | ||

| 8. | "Bitch (skit)" | 0:19 | ||

| 9. | "Role Model" |

|

| 3:25 |

| 10. | "Lounge (skit)" | 0:46 | ||

| 11. | "My Fault" |

| 4:01 | |

| 12. | "Ken Kaniff (skit)" | 1:16 | ||

| 13. | "Cum on Everybody" (featuring Dina Rae) |

| 3:39 | |

| 14. | "Rock Bottom" | Bass Brothers | 3:34 | |

| 15. | "Just Don't Give a Fuck" |

| 4:02 | |

| 16. | "Soap (skit)" | 0:34 | ||

| 17. | "As the World Turns" | 4:25 | ||

| 18. | "I'm Shady" |

| 3:31 | |

| 19. | "Bad Meets Evil" (featuring Royce da 5'9") |

|

| 4:13 |

| 20. | "Still Don't Give a Fuck" |

| 4:12 | |

| Total length: | 59:39 | |||

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hazardous Youth (acapella version)" | 0:47 |

| 2. | "Get You Mad" | 4:21 |

| 3. | "Greg (acapella version)" | 0:53 |

| 4. | "Just Don't Give a Fuck (music video)" | |

| 5. | "My Name Is (music video)" | |

| 6. | "Guilty Conscience (music video)" | |

| 7. | "Role Model (music video)" | |

| 8. | "The Slim Shady LP (Live & Studio Footage)" |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 21. | "Hazardous Youth (acapella version)" | 0:44 |

| 22. | "Get You Mad" (with Sway and King Tech & DJ Revolution) | 4:22 |

| 23. | "Greg (acapella version)" | 0:52 |

| 24. | "Bad Guys Always Die" (with Dr. Dre) | 4:39 |

| 25. | "Guilty Conscience (radio version)" (featuring Dr. Dre) | 3:19 |

| 26. | "Guilty Conscience (Instrumental)" (featuring Dr. Dre) | 3:20 |

| 27. | "Guilty Conscience (acapella version)" (featuring Dr. Dre) | 3:16 |

| 28. | "My Name Is (Instrumental)" | 4:29 |

| 29. | "Just Don't Give a Fuck (acapella version)" | 3:35 |

| 30. | "Just Don't Give a Fuck (Instrumental)" | 4:08 |

| Total length: | 36:00 | |

Notes

- ^[a] signifies a co-producer.

- ^[b] signifies a pre-production.

- On the clean version of the album, "Bitch", "Cum on Everybody", "Just Don't Give a Fuck", and "Still Don't Give a Fuck" are respectively retitled "Zoe", "Come on Everybody", "Just Don't Give", and "Still Don't Give".

- Some online platforms (such as Myspace) include an alternate clean version of the album which completely removes the song "Guilty Conscience".

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[118] | 8× Platinum | 560,000‡ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[119] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[120] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[121] | Platinum | 15,000^ |

| South Africa (RISA)[122] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[123] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[125] | 4× Platinum | 1,100,000[124] |

| United States (RIAA)[128] | 5× Platinum | 6,597,000[126][127] |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[129] | Platinum | 1,000,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Smith, Chris (2009). 101 Albums that Changed Popular Music. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195373714. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Peters, Mitchell (March 5, 2016). "Eminem Plans to Re-Release 'The Slim Shady LP' on Cassette". Billboard. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Brown, Preezy (February 23, 2019). "7 reasons Eminem's 'The Slim Shady LP' is a classic". Revolt. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Bozza 1999

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bozza, Anthony (November 5, 2009). "Eminem Blows Up". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Eminem – Biography". AllMusic. AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ Bozza, Anthony (April 29, 1999). "Eminem Blows Up". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Montgomery, James (December 14, 2004). "Studio Where Eminem Worked On Shady LP Up For Auction". MTV News. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Bozza, 2003. p. 24

- ^ Stubbs, 2006. p. 58

- ^ Fu, Eddie (February 23, 2019). "Knowledge Drop: Marilyn Manson Passed On Eminem's "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" Because It Was "Too Misogynistic"". Genius. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Stubbs, 2006. p. 68

- ^ Bozza, 2003. p. 43

- ^ Chonin, Neva (May 8, 1999). "Rage Against the Past / Eminem is a former skinny white kid who raps with a vengeance". SFGATE. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ McCollum, Brian (August 6, 2015). "Kid Rock before the fame: The definitive Detroit oral history". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ a b c IGN Staff (November 12, 2004). "The Slim Shady LP - Over-the top horror-core with fat beats". IGN. News Corporation. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Bozza, 2003. p. 25

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Kyle (February 23, 2011). "Eminem's The Slim Shady LP, 12 Years Later". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Slim Shady LP – Eminem". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c Sheffield, Rob (April 1, 1999). "The Slim Shady LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ Stubbs, 2006. p. 78

- ^ Stubbs, 2006. p. 84

- ^ Pareles, Jon (April 17, 1999). "Pop Review; A Rapper More Gauche Than Gangsta". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Kot, Greg (April 9, 1999). "Feeding the Frenzy". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Stubbs, 2006. p. 75

- ^ a b c Stubbs, 2006. p. 81

- ^ Verrico, Lisa (May 20, 2000). "Bite me". The Times. News Corporation.

- ^ a b c d Hilburn, Robert (May 14, 2000). "Has He No Shame?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c Brockes, Emma (November 12, 1999). "Cover story: Emma Brockes meets Eminem". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Alvarez, Gabriel (December 6, 2011). "The 50 Greatest Hip-Hop Skits - Eminem "Public Service Announcement"". Complex. Complex Media. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Hasted, 2011. p. 111

- ^ Bozza, 2003. p. 49

- ^ a b c d Wiederhorn, Jon (December 10, 2001). "Alleged Bully From Eminem's 'Brain Damage' Files $1 Million Suit". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on February 2, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ Hartigan, 2005. p. 162

- ^ Hartigan, 2005. p. 161

- ^ Kyles, Kyra (March 14, 1999). "Eminem, 'The Slim Shady LP' (Aftermath/Interscope)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (2000). "CG Book '90s: E". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-312-24560-2. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ a b Browne, David (March 12, 1999). "The Slim Shady LP". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Baker, Soren (February 21, 1999). "Eminem 'Slim Shady LP' Aftermath / Interscope". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Eminem: The Slim Shady LP". Melody Maker: 36. May 1, 1999.

- ^ "The Slim Shady LP". NME. April 13, 1999. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Hoard, Christian (2004). "Eminem". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 276–77. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b Rubin, Mike (May 1999). "Eminem: The Slim Shady LP". Spin. 15 (5): 148. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Rodman, Gilbert (2006). "And Other Four Letter Words: Eminem And The Cultural Politics Of Authenticity". Popular Communications: 100.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (February 23, 1999). "Eminem: The Slim Shady LP - Review". The A.V. Club. The Onion, Inc. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Dafoe, Chris (April 16, 1999). "The Slim Shady LP - Review". The Globe and Mail. Phillip Crawley.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (March 23, 1999). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Serpick, Evan. "Eminem - Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: The Slim Shady LP - Eminem". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "100 Best Albums of the '90s: Eminem - The Slim Shady LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 300-201 | NME". NME. October 24, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ "[BLENDER: Articles]". April 19, 2002. Archived from the original on April 19, 2002. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ Alvarez, Gabriel (December 6, 2011). "The 50 Greatest Hip-Hop Skits - Eminem "Ken Kaniff"". Complex. Complex Media. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "The 300 best albums of the past 30 years(1985-2014)". Spin. May 11, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Kid Rock, Eminem, Stevie Wonder, and CeCe Winans Among the Winners at the 2000 Detroit Music Awards". NY Rock. April 17, 2000. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Adaso, Henry. "100 best hip hop albums". About.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (May 19, 2021). "Xgau Sez: May, 2021". And It Don't Stop. Substack. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Weingarten, Charles Aaron, Mankaprr Conteh, Jon Dolan, Will Dukes, Dewayne Gage, Joe Gross, Kory Grow, Christian Hoard, Jeff Ihaza, Julyssa Lopez, Mosi Reeves, Yoh Phillips, Noah Shachtman, Rob Sheffield, Simon Vozick-Levinson, Christopher R.; Aaron, Charles; Conteh, Mankaprr; Dolan, Jon; Dukes, Will; Gage, Dewayne; Gross, Joe; Grow, Kory; Hoard, Christian (June 7, 2022). "The 200 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Basham, David (February 28, 2002). "Got Charts? Expect 'O Brother' Sales Boost After Unexpected Win". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c "The Slim Shady LP - Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Gold & Platinum RIAA Certifications 2000". Recording Industry Association of America. November 14, 2000. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Chart History: Eminem - My Name Is". Billboard. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Chart History: Eminem - Guilty Conscience". Billboard. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Chart History: Eminem - Just Don't Give a Fuck". Billboard. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ Tardio, Andres (November 20, 2013). "Hip Hop Album Sales: Week Ending 11/17/2013". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Certification - March 2001". Canadian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ^ "Certified Awards Search" Archived January 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ "Artist Chart History: Eminem". The Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Australiancharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "ARIA Charts - Accreditations - 2003 Albums" Archived February 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ a b "Dutchcharts.nl – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "NVPI, de branchevereniging van de entertainmentindustrie: Goud/Platina" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c Hasted, 2011. p. 123

- ^ a b c Huxley, 2000. p. 79

- ^ a b c Hasted, 2011. p. 125

- ^ a b c Bozza, 2003. p. 69

- ^ a b Verrico, Lisa (January 28, 2001). "INTERVIEW: Who's the real Slim Shady?". Scotland on Sunday. Johnston Press.

- ^ a b "Eminem safe from bully's lawsuit". BBC News. April 16, 2005. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c Wiederhorn, Jon (September 17, 2003). "Eminem Gets Sued ... By A Little Old Lady". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Harlene Stein v. Marshall B Mathers, et al". Plainsite.org. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Eminem The Slim Shady LP - ltd edition 2-CD UK DOUBLE CD (177021)". Eil.com. February 8, 2001. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ "The Slim Shady LP (Expanded Edition) by Eminem on Apple Music". iTunes. February 22, 2019. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Urban Chart – Week Commencing 12th February 2001" (PDF). The ARIA Report (572): 18. February 12, 2001. Retrieved April 15, 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP Special Edition". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP Special Edition". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eminem Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "R&B : Top 50". Jam!. May 22, 2000. Archived from the original on May 23, 2000. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 41, 2000". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "エミネムのアルバム売上ランキング". Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011. Oricon Archive. Slim Shady LP. June 5, 2002

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP Special Edition". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eminem | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Official R&B Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eminem Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eminem Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eminem Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "RPM 1999: Top 100 CDs". RPM. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1999". Official Charts Company. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1999". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 1999". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Albums of 2000". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2000". Official Charts Company. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Billboard year end charts 2000". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006.

- ^ "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 2000". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2001". Ultratop. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 R&B; albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on October 12, 2003. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 rap albums of 2002 in Canada". Jam!. Archived from the original on October 12, 2003. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2001". Official Charts Company. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 2, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2024 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Eminem – Slim Shady". Music Canada.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Eminem – Slim Shady" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved November 9, 2021. Enter Slim Shady in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 2001 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Recorded Music NZ.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link)[dead link]THE FIELD archive-url MUST BE PROVIDED for NEW ZEALAND CERTIFICATION from obsolete website. - ^ "Eminem heading to South Africa for two shows". The Times. November 18, 2013. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('The Slim Shady LP')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (September 5, 2018). "Eminem's Top 10 biggest albums on the Official Chart". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ "British album certifications – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "Eight Eminem Albums Charted On Billboard 200 This Week". XXL. Harris Publications. November 13, 2013. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ David, Barry (February 8, 2003). "Shania, Backstreet, Britney, Eminem and Janet Top All Time Sellers". Music Industry News Network. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- ^ "American album certifications – Eminem – The Slim Shady LP". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2007". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry.

Works cited

[edit]- Bozza, Anthony (2003). Whatever You Say I Am: The Life and Times of Eminem. New York, New York, United States: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 1-4000-5059-6.

- Hartigan, John (2005). Odd Tribes: Toward a Cultural Analysis of White People. Duke University Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8223-3597-9.

- Hasted, Nick (2011). The Dark Story of Eminem. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-458-2.

- Huxley, Martin (2000). Eminem: Crossing the Line. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-26732-0.

- Stubbs, David (2006). Eminem: The Stories Behind Every Song. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-946-6.